When the Portobello farmhouse featured in a watercolour in 1864, shortly before its demise, the only other building on the lane north of the newly opened Hammersmith and City railway line was the Notting Barn Lodge, situated on Portobello Lane at the future junction of Cambridge Gardens. This lodge stood by the entrance to the lane leading to the other farm of the same name, to the west.

Florence Gladstone wrote in ‘Notting Hill in Bygone Days’: ‘There seems to be a natural break where the railway embankment crosses Portobello Road. At this point the old lane was interrupted by low marshy ground, overgrown with rushes and watercress.’ But within a few years of the painting the last remaining fields of Portobello farm would become the streets of the Golborne ward.

Alongside the railway line boundary of the Golborne and Colville wards, Acklam Road was built in the late 1860s and stood for a hundred years, before being demolished to make way for the Westway flyover in the late 1960s.

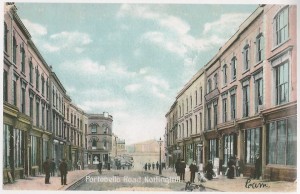

The road took its name from the Acklam village, now in Middlesborough, which like Rillington and Ruston is close to the Yorkshire country seat of the North Kensington developer Colonel St Quintin. The old street featured the Duke of Sussex pub on the corner of Portobello Road, currently an open-air market area by the entrance to the Acklam Village farmers; market. Acklam Road was built under the direction of the Land and House Investment Society Ltd.

At the beginning of the 20th century, on Charles Booth’s ‘Life and Labour of the People of London’ map, conditions on Acklam Road were assessed as fairly comfortable with some poverty and comfort mixed on the Portobello corner.

In the 1914 street directory, the south side was occupied by Jane Wood’s laundry at number 2, the coal dealer John Richards at 18, John Getgood & Son’s loan office at 52, the greengrocer Henry Day and general dealer Albert Moore at 106, the bootmaker Albert Apps at 108 and the newsvendor Henry Temperton at 110. On the north side there was the timber merchant William Wilkins at number 1, Harrison & Co builders at 17, the French polisher John Hobbs at 29, who was still going in the 1930s, the bricklayer George Reeve at 43, Rose Heffernan’s chandler’s shop at 51, the confectioner Alfred Bradley at 63, the beer retailer Florence Mulberry at 65 and tobacconist Emma James at 77.

By 1935 number 1 had become J Sandell & Co timber merchants and remained so into the 60s, William Croft was running the chandler’s shop at 51, Robert Broom was the beer retailer at 65, accompanied by the boot repairer George Hawkes, 77 was George England’s confectioner’s shop, 110 was Ernest Butcher’s newsagents till the 60s, and 114 by the railway footbridge was the Pembroke Athletic Club boxing gym. In the 60s the scrap metal merchants Acklam Metals were established at number 20 on the south side, 51 was David James & Son grocery shop and the beer retailer at 65 was Kenneth Stokes.

From the 19th century up until 1965, number 3 Acklam Road, near the Portobello junction, was occupied by the Bedford family. When the Westway construction work began they sold up and moved to south London. Anne Bedford (now McSweeney) is pictured in the 60s standing outside the house with her back to the south side of the street, shortly before it was demolished, behind which was the tube line. Her grandparents were photographed on their wedding day in 1910 in the top floor front room, next to their piano. In the early 70s the house was taken over by the North Kensington Amenity Trust and became the Notting Hill Carnival office before its eventual demolition.

Anne McSweeney: ‘My memories are all happy from living there. I now know that the conditions were far from ideal but then I knew no different. There was no running hot water, inside toilet or bath, apart from the tin bath we used once a week in the large kitchen/dining room. Any hot water needed was heated in a kettle. I wasn’t aware that there were people not far away who were a lot worse off than us, living in poverty in houses just like mine but families renting one room. We did have a toilet/bathroom installed in 1959, which was ‘luxury’. My grandparents and uncle lived on the top floor, and mum, dad and I lived below them with a bedroom at the front at street door level, which my uncle used. The room at street level to the rear was used by my father as a workshop and later became the bathroom.

‘When the plans for the Westway were coming to light, we were still living in the house whilst all the houses opposite became empty and boarded up one by one. We watched all this going on and decided that it was not going to be a good place to be once the builders moved in to demolish all the houses and start work on the elevated road. Dad sold the house for a fraction of what it should have been worth but it needed too much doing to it to bring it to a good living standard. We were not rich by any means but we were not poor. My grandmother used to do her washing in the basement once a week by lighting a fire in a big concrete copper to heat the water, which would have been there until demolition. There was also a huge wood and metal mangle with wooden rollers to wring out the wet clothes by turning the handle.

‘For the first 12 years of my life, going to the loo would have meant several flights of stairs to the basement and outside into the yard, not too good, especially in winter. We were the only house not to have a garden as we were beside the timber yard, whose yard sloped and therefore tapered the size of the rear of the house so we only had a very small yard, but we did have the biggest house in the street as we had the extra rooms over the timber yard entrance. Coal being delivered is another memory for me, as the coalman would come round with sacks on his cart and open the manhole cover on the pavement and whoosh the coal into the cellar below. As a child I would be asked to go to the basement to fill a bucket with coal for use upstairs and I remember that I would frighten myself thinking that there could be someone or something lurking in the shadows – all quite dimly lit down there so I used to sing or make noise as I got to the basement and opened the coal cellar door.

‘When we moved from number 3, I remember the upright piano that my grandparents used to play – and me of sorts – being lowered out of the top floor and taken away, presumably to be sold. I used to play with balls up on the wall of the chemist shop on the corner of Acklam and Portobello. We would mark numbers on the pavement slabs in a grid and play hopscotch. Roller-skating, skipping ropes, scooters and tricycles were other outside activities. I once was swinging on the gate of the basement over the basement steps – we used to call it the airy – and the gate came off and I ended up at the bottom of the steps. Dad took me to the chemist and I remember sitting on a bench while the pharmacist cut away part of my hair to treat a cut on the back of my head. At the Portobello and Acklam Road corner, on one side there was the Duke of Sussex pub, on the other corner, a chemist, later owned by a Mr Fish, which I thought was amusing. When I was very young I remember every evening a man peddling along Acklam Road with a long thin stick with which he lit the streetlights.’

Michelle Active who lived at 33 Acklam Road: ‘I was 6 then and sort of remember the goings on but didn’t really understand. 6 of us lived in a one-bed basement flat on Acklam Road. When they demolished it we moved to a 4-bed maisonette on Silchester Estate and I thought it was a palace, two toilets inside, a separate bathroom that was not in the kitchen, absolute heaven.’

Before Westway construction work began in 1966, the site of the south side of Acklam Road towards Westbourne Park hosted the London Free School adventure playground. This hippy community action project was inaugurated with an auto-destructive art performance by Gustav Metzger, consisting of a pile of rubbish that was set alight by local children. The Westway site was called ‘the dark side of the moon’ by Emily Young (of Pink Floyd’s ‘See Emily Play’ fame) in Jonathon Green’s ‘Days in the Life’ counter-culture oral history book: “They were starting to build the motorway and they’d knocked down this run of houses. It was the dark side of the moon, the other side of wonderful Britain. It was the Martian wasteland. There were dead donkeys lying around, and dead people, a dead baby one time, a very weird place, desolation. And we’d have happenings; huge bonfires and musicians would come and Dave Tomlin played the saxophone and wrote poems and we’d take a lot of acid.”

The Free School adventure playground was founded by Adam Ritchie, a local activist and photographer who had been in New York at the time of community action in Tompkins Square that saved a play area from redevelopment. On the site of the Westway, he recalled ‘complex, wonderful structures’ being created by the local children, after he left out a hammer, saw and nails for them to use. In ‘The Politics of Community Action’ description by Jan O’Malley: ‘Steps were built down from the road to give children access and rough structures and swings were knocked together.’

At the last London Free School project meeting, as construction work began in September 1966, Adam Ritchie proposed continuing the adventure playground part of the project under the flyover. The North Kensington Playspace Group proto-Westway Trust was subsequently formed by him and John O’Malley of the Notting Hill Community Workshop, with the aim of establishing a permanent adventure playground on Acklam Road. At this stage according to Jan O’Malley: ‘No one was certain about the use planned for the motorway space. While the chairman of the GLC Highways Committee had a vague idea that the space was to be used for recreation, the engineers building it believed the plans were to use it for warehousing and a car park.’

Dave Robins wrote in the Notting Hill ‘Interzone’ issue of International Times in May 1968: ‘The area could congeal into a genuinely depressed ghetto, people’s social and economic needs being overshadowed by the gigantic inhuman motorway. This is what happened after the building of over-head railways in Chicago and New York. Local politicians could seize this opportunity to turn Notting Hill into Britain’s first US style black ghetto (if it isn’t that already). A lot may depend on the use of the huge arches or spans which carry the motorway… If the spans are given over to the community, the possibilities for further creative extensions to the children’s adventure playground, already under way in Westbourne Park, are total. At the moment, the Council has provisionally accepted the £½ million scheme of amenities, play facilities and open space use of the arches and spans under the Western Avenue Extension put forward by Adam Ritchie, John O’Malley and their North Kensington Playspace Group.’

As the Playspace Group was renamed the Motorway Development Trust in late 1968, their plan outlined by Robin Moore was to create: “a kind of community strip, a bustling social market place, complementing the commercial activity of Portobello Road.” The proposed amenities for the Acklam Road bays were a public laundry, café, health centre, nursery school, pre-school playgroup, sport area and adventure playground. After the Motorway Development Trust established the first adventure playground under the flyover on St Mark’s Road, with the assistance of the Westway contractors Laing Construction, for the next summer holidays in 1969 the Acklam Road Adventure Playground was opened in 6 bays east of Portobello Road. The following year it was established as a permanent playground with a hut.

Adam Ritchie says of his 1969 Acklam playground photographs displayed on the site in Steve Mepsted’s Orphans mural exhibition: “I was part of a whole lot of people who got these playgrounds going in the first place and got them under the motorway, because it was supposed to be a car park for commuters. So we rigged up scaffolding and there was stuff going on, and the kids made lots of things – constructions. In one of them there’s a huge packing case that we got and the kids were making houses or whatever they were doing out of it. The people in them, the kids are absolutely beautiful, they just look as if they’re free and having a wonderful time.”

During the four years of construction work, for the remaining inhabitants of the north side of Acklam Road and the other surviving terraces close to the flyover, ‘continuous noise and dirt from heavy lorries and machinery became a familiar and unwelcome part of life.’ The sound of the Westway being built was described by Eileen Wright in ‘Taking on the Motorway’: “There was a terrible noise for weeks when they were pile-driving. They started at 6 O’clock in the morning – sometimes it went on all night. You think the whole city is being bombarded beneath you.”

From 1968 through the 70s, the wall alongside the Hammersmith and City line beneath the Westway between Portobello Road and Westbourne Park featured graffiti by the Situationist King Mob group that read: ‘Same thing day after day – Tube – Work – Diner (sic) – Work – Tube – Armchair – TV – Sleep – Tube – Work – How much more can you take – One in ten go mad – One in five cracks up.’

MDT plan

On July 28 1970 the Westway, A40 Western Avenue Extension flyover between White City and Paddington, at two and half miles, the longest elevated road in Europe at the time, was opened by Michael Heseltine, the parliamentary secretary to the transport minister. The opening ceremony was famously accompanied by a protest over the re-housing of the last residents alongside the road. As demonstrators disrupted the ribbon cutting, a banner was unfurled on Acklam Road, looking on to the flyover, demanding: ‘Get Us Out of this Hell. Re-house Us Now’.

Michael Heseltine told the press: “There are two sides to this business. One is the exciting road building side… but there is also the human side of this thing, and how huge roads like this affect people living alongside them. You cannot but have sympathy for these people.” The Standard reported that: ‘the ministerial cavalcade later drove the length of the twin dual-carriageway running from Paddington to White City. On the way it passed Acklam Road, where bedrooms of houses are less than 50 feet from the elevated section of the road. Here the GLC is proposing to spend £250,000 buying 42 houses which have been ‘blighted’, demolish them and turn the land acquired into a buffer state.’

The Acklam Road residents’ representative George Clark protested to the Transport Minister John Peyton (who said he couldn’t attend the opening because he had to be at a cabinet meeting): “I want to make a statement to the minister about the hell on earth in North Kensington. During the 5 years it has taken to construct this engineering marvel, the lives and social conditions of the residents of Acklam Road and Walmer Road have been made hell upon earth. For these people the new urban highway is a social disaster.”

The Westway opening protest developed into a local dispute between Walmer Road and Acklam Road, as George Clark was blamed for holding up the re-housing of the former tenants in favour of the latter. International Times accused him of ‘diverting justifiable community anger from radical action into harmless words.’ In Jan O’Malley’s ‘Politics of Community Action’: ‘Clark, who had been invited to the official opening reception representing the tenants of Acklam Road, tried to welcome the demonstrators as his followers. But the people from Walmer Road would have none of that, since only the day before the tenants from Acklam Road had refused to help them in their struggle, once their own fight for re-housing was won. While the people were being arrested and the demonstration was going on, George Clark was staging a pray-in thanksgiving for the re-housing of Acklam Road.’

As 47,000 vehicles a day began ‘cruising through the rooftops of North Kensington’, negotiations between the Motorway Development Trust and the Council resulted in the inauguration of a new trust with a half-Council/half-community management committee in 1971. Andrew Duncan wrote in his introduction to ‘Taking on the Motorway’: ‘Out of a 4-year campaign, North Kensington Amenity Trust was set up in partnership with the local authority in response to two demands: The mile strip of land under the motorway which lay within the borough’s boundaries should be used to compensate the community for the damage and destruction caused by the road; and the 23 acres should be held in trust to ensure that local people would be actively involved in determining its use. The story of the trust is one of conflict, for it was born out of bitter clashes between an angry local community and the two planning authorities that gave consent to the motorway intruder – the GLC and the RBK&C. But it is also a story of hope…’

Anthony Perry, the first director of North Kensington Amenity Trust, was a former film producer who had worked on the Beatles’ ‘Yellow Submarine’. He concluded that developing the Westway land ‘would call for qualities not unlike those needed for producing a film’, went for the job and got it. In his ‘A Tale of Two Kensingtons’ diary of the trust’s first 5 years from 1971 to 76, he pondered: ‘What is the Amenity Trust? In the very simplest terms, it is a charity that has been set up to develop the 23 acres of land under the elevated motorway in North Kensington in the interest of the community. No thought was given to the social implications for this working-class neighbourhood at the time the motorway was planned. The trust was set up in response to the great energy and pressure of a small number of local people.

Acklam protest

‘When I applied for the job I thought I would dazzle the interviewing committee by telling them I had been out in the streets asking local people about the motorway land and what they would like to see it used for. This would please the local people who had fought for the trust to be established and not frighten the Tory councillors. And it wasn’t cynical – I wanted the job of developing the 23 acres of empty land and was sincerely curious to know what local people thought. It was, after all, their neighbourhood, which had been ripped in half to build the road. So that’s what I did. I borrowed a Nagra from my old film company and stood on the corner of Acklam Road and Portobello and stuck my microphone under the noses of startled passers-by. The first man I stopped said: “It’s no good asking me, mate, I only got out of the nick this morning”, and hurried on. But most people looked blank or maybe ventured “car parks?”

‘The council wanted me to take an office at the town hall but it was essential I be on the spot so I occupied an empty house waiting for demolition, on the corner of Portobello and Acklam Road, and set up shop on May 28 1971 with the help of Pat Smythe, a tough resourceful member of the management committee who had set up the first adventure playground in Telford Road. 3 Acklam Road was one of a row of houses due to be demolished as being too close to the motorway. I subsequently got them reprieved and we did some repairs and re-wiring and gave rooms to local groups. Our office was the one overlooking the junction with Portobello Road.’

Compiled by Tom Vague

1 comment

I loved reading your comments on Acklam road I lived there with my family first at 84 where I lived with my parents and 4 sisters. Tragically my parents were both killed in a car accident on 10 January 1960. We were then cared for by my aunt and uncle. In 1963 we moved across the road to the shop at 65 which my uncle bought from Kenneth stokes , I must say your article made me very nostalgic

Thank you