CHAPTER I – Introduction

’A massive gleaming financial centre surrounded by a shanty town’ was how a local man described the Isle of Dogs in 1986, commenting on the stark contrast that had emerged between the new large-scale office developments on the former dock estate and the public housing which occupied much of the remainder of the area. Such a contrast is not new to Poplar, which has attracted a succession of developments notable for their scale and originality: Blackwall Yard in 1614, the Brunswick Dock in 1789–90, and the West India and East India Docks between 1800 and 1806 were all, when they were built, unusual and even unprecedented for their size and ambition. But accompanying these large-scale commercial complexes were modest and mundane developments that were typical of London’s East End riverside: shipbuilding yards, metal-working and foodprocessing factories, noxious establishments such as tar and chemical works, and much substandard housing, some of it of a distinctly squalid nature.

The character of the area has been determined not only by such developments, but also by the extent and scale of the topographical changes which it has experienced. Indeed, today the pre-1939 fabric has all but disappeared, and is represented by only a very few dock buildings, churches and public houses, pockets of nineteenth-century housing, and a range of public buildings. The earlier industrial sites, most of them around the riverside, and the nineteenth-century housing have been swept away by a variety of processes – bomb damage during the Second World War, the replacement of poor houses by local authorities, and by economic change and redevelopment following the closure of the docks in the 1970s. In consequence, though the dominant elements in Poplar at the end of the twentieth century are the West India and Millwall dock basins, the rest of the landscape is made up of public housing, chiefly of the 1950s to 1970s, and commercial buildings and private residential schemes erected during the Docklands boom of the 1980s. Although physical traces of the earlier phases of development survive in parts of the area, in others later changes have modified the earlier landscape so much that it is no longer recognizable.

Physically, the area consists of three parts. The northernmost one is a terrace of flood-plain gravel, at no point more than 25ft above sea level, although with sufficient undulations for one section of Poplar High Street to be known as Poplar Hill. To the south of the High Street the land falls sharply away to the Isle of Dogs, a lowlying marshland of alluvial soil, underlaid by clay or mud, in the meander loop of the Thames. This area – also known as the Island – covers more than two-thirds of the parish, but because of the marshy ground and the costs of drainage and flood prevention works it was the last part to be developed. Blackwall, the easternmost part of the parish, is also a low-lying area, much of it forming a peninsula of land between the meanders of the River Lea and the Thames.

The parish’s long riverside on the Thames and the Lea was the dominant influence on its economy until the late twentieth century. Nevertheless, the general pattern of development established by the late fifteenth century remained largely unchanged until after 1800, and much of the riverfront was not developed until the period of expansion during the mid-nineteenth century. There was settlement along the line of Poplar High Street on the low ridge of land overlooking the Isle of Dogs and, from the seventeenth century, at Blackwall, which had become an embarkation and disembarkation point for passengers wishing to avoid the river journey around the Island (fig. 1). An earlier settlement in the Isle of Dogs had been abandoned in the mid-fifteenth century. Ship repairing was established at Blackwall before 1500, and the area was chosen by the East India Company for its shipbuilding yard, constructed there between 1614 and 1617. The yard was the largest commercial employer of labour in the London area, and remained the basis of Poplar’s economy throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In private hands from the 1650s, it was a major builder of East Indiamen and warships and its fortunes fluctuated with the demand for such vessels. By the late eighteenth century the yard was so prosperous that its owner, John Perry, was able to construct the Brunswick Dock here in 1789–90. Because of its size, its construction attracted widespread interest and admiration. At this time, the district’s predominant industries were still maritime, the chief exceptions being copperas manufacture on a site at Blackwall, from the late seventeenth century until the early nineteenth century, a white-lead plant at Limehouse Hole (1717–80), and a potash manufactory in northern Poplar, established in 1778. Such development as there had been by the late eighteenth century, other than in the High Street, had been in the Limehouse Hole area and, more modestly, at Blackwall.

The early nineteenth century saw a major and dramatic change, with the construction between 1800 and 1806 of the West India and East India Docks and the City Canal. The West India Dock Company alone purchased 17 per cent of the area covered by the hamlet of Poplar and Blackwall (from 1817 the parish of All Saints). With the docks came greater economic activity and communications, with an increase in river traffic between the Isle of Dogs and the wharves along the City’s riverside as goods were shipped out of the docks, and the construction of road links, principally the Commercial, West India Dock and East India Dock Roads. In addition, the Iron Bridge, opened in 1810, was the first bridge over the lower section of the Lea, providing road communication from Poplar into Essex. Until then the hamlet had been a dead-end as far as land transport was concerned.

Though the presence of the docks stimulated some grandiose, yet abortive, schemes for the Isle of Dogs in the subsequent decades, they produced relatively little actual development. Indeed, the input from the selfcontained dock complexes into the local economy was limited, because the goods brought into the East India Docks were immediately transported into the City, the West India products were not processed in Poplar, and the business community controlling the trade remained in the City. The dock companies made an impact chiefly as a market for tradesmen supplying them and their employees, and as large-scale employers of casual labour, for they employed relatively few permanent staff in the docks. The numbers required fluctuated; in the middle of the nineteenth century the West India and East India Docks employed between 1,300 and 4,000 men, drawn both locally and from other parts of east London, on both sides of the Thames.

The construction of the docks did not produce a rapid expansion of industry, nor a change in its complexion. The industrial and riverside developments continued to creep southwards from Limehouse Hole along Millwall, but southern Millwall and the south-eastern part of the Isle of Dogs, the future Cubitt Town, remained undeveloped until the middle of the century. The additional population was chiefly accommodated in new housing along, and off both sides of, East India Dock Road, and in the area between Poplar High Street and East India Dock Road.

Population growth and industrial expansion continued steadily in the 1820s and 1830s, producing an optimism expressed in the comment, made in 1838, that in these times of Improvement and enterprise Poplar is happy in having so many advantages from its locality and extended River frontage’. The slow growth of the 1840s was followed by the major boom of the century, in the 1850s and early 1860s. This was part of a wider economic expansion, reflected in Poplar by the development of the shipbuilding industry, further fuelled by orders during the Crimean War of 1854–6 and the American Civil War of 1861–5. These conflicts greatly increased the demand for ships, as did the adoption by the major navies of iron steamships to replace wooden sailing ones. The boom years, which continued after the end of the American Civil War, also saw the construction of the Millwall Docks in 1864–7, although only a part of the proposed scheme was built. The inland sites were not attractive to industry, which was still concentrated around the riverside, and so there was sufficient undeveloped land in the centre of the Isle of Dogs for the new docks 60 years after the first dock boom. During these years of economic growth, new housing was built in the remaining open space in the northern part of the parish, and on the Isle of Dogs, which had hitherto seen little housing development.

In 1866 Overend Gurney & Company, bankers and money dealers, failed. The repercussions were widespread and brought the boom to an abrupt halt, in Poplar as elsewhere. Over-extended credit had left the local economy in a perilously exposed position and the financial crisis had a cumulative and ultimately catastrophic effect. Many of the firms on the riverside collapsed, with shipbuilders, some of whom had borrowed heavily from Overend Gurney & Company, particularly badly affected.

Members of London’s fashionable society had turned out in large numbers to witness the opening of Brunswick Dock and the West India and East India Docks, but the area attracted little attention thereafter, apart from the crowds, which attended the attempt in 1857 to launch Brunel’s Great Eastern at Millwall. The distress caused by the slump of 1866–7 was so great, however, that widespread interest and sympathy was aroused. The Times reported that the recession in the shipbuilding industry was such that it amounted to almost temporary extinction’ and that far too much labour had been brought into the area during the ’bubble period’ than could be found employment in normal circumstances. The plight of the many unemployed was advertised in the newspapers, and local businessmen set up the East End Emigration Committee to arrange free passages to North America for the jobless and their families.

In due course, the local economy revived, although the Thames shipbuilding industry was much reduced in size. The numbers employed in shipbuilding and marine engineering on the Thames had increased from an estimated 6,000 men in 1851 to 27,000 in 1865, but fell to 9,000 by 1871, and to 6,000 by 1891. Some yards were able to continue in business until the early twentieth century by taking specialized work, and the industry experienced a brief revival during the First World War, but most of the shipbuilding capacity on the Thames was lost to the Clyde, where costs were lower. Another significant loss to the local economy was the closure in 1874 of the glassworks, which had been established in Orchard Place in 1835. There was also a shift away from engineering, as other, lighter, manufacturing trades and the chemical industry, which was already well established, became more prominent. The mid-century boom had drawn much skilled labour into the area, but the industries that were prominent later in the century drew upon unskilled labour, including women and girls. Heavy industry did not completely desert the area, however, and iron-and-steel firms such as Shaws, Westwoods, Brown Lenox and Richard Thomas & Baldwins remained major local employers until the late twentieth century. Wharfingers took over a number of former industrial premises, and wharfage, especially its shabbier and messier branches, became characteristic of the area. The riverside in the late nineteenth century was dominated by shipyards, oil wharves, sack-cleaning works, paint, varnish and chemical works, jam and preserves factories, and a host of miscellaneous enterprises, carried on in a seemingly haphazard jumble of sheds, workshops, warehouses and yards.

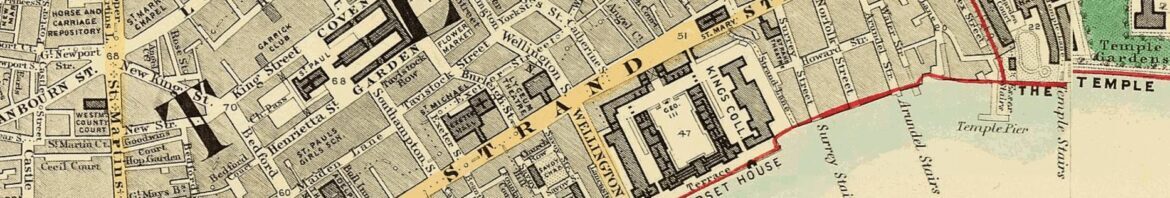

Figure 1:

Poplar, Blackwall and the Isle of Dogs in 1703. Reproduced from Joel Gascoyne’s Survey of the Parish of St Dunstan’s, Stepney

The crash of 1866 brought house-building to a sudden halt. Moreover, emigration from the area resulted in large numbers of empty houses, particularly on the Isle of Dogs, where there were almost 800 empty dwellings in 1868, approaching a half of the total. Although an economic revival followed the slump of the late 1860s, the Island was not well placed to benefit from it and there were still 262 vacant houses in 1871. In such circumstances, building took some time to resume and the developments which were proposed either failed to attract investment or took a long time to get under way. Land prices fell considerably in the aftermath of the crash and some sites did not attract purchasers. House-building in the area was now largely taking place away from the Thames, in Bow and Bromley: in 1863–83, 1,867 notices were received by the District Board of Works relating to the building and drainage of new houses and other property in Poplar, but 9,719 in Bow and Bromley. There was a revival of house-building in the 1880s and 1890s, with a few new developments, but much more in the way of infilling, completing street frontages that were already partially built up. Almost all of the housing erected in the last 20 years of the nineteenth century was on the Isle of Dogs; the earlier developed districts in Poplar and Blackwall had little or no space left for building (fig. 2).

The population of the hamlet rose fourfold between the early seventeenth century and the beginning of the first dock boom, to a figure of 4,493 by 1801. It rose sharply during the first two decades of the nineteenth century, to 7,708 in 1811 and 12,223 in 1821, and continued to grow throughout the remainder of the century, albeit erratically. The most dramatic period of growth came during the boom years of the 1850s and early 1860s, which saw an increase of 53 per cent between 1851 and 1861, from 28,342 to 43,529. The pace of growth then tailed off. The population of Poplar and Blackwall peaked around 1880, while that of the Isle of Dogs continued to rise until the turn of the century. The peak figure for the whole parish was reached in 1901, when there were 58,814 inhabitants. It was multiplefamily occupation of existing houses which provided much of the accommodation for the extra numbers in the parish in the late nineteenth century.

Despite the modest revival of house-building in the late nineteenth century, the earlier prosperity and optimism had not returned and Poplar was now perceived as one of the poorest districts of the capital. The West India and East India dock companies had been at their most prosperous in the first quarter of the century, but faltered thereafter, following the expiration of the West India Dock Company’s monopoly in 1823 and that of the East India Dock Company in 1827. A period of adjustment ensued and the companies merged in 1838. The East and West India Dock Company then enjoyed a prosperous period during the middle decades of the century, but it was not without difficulties. One of the long-standing problems was the effect of the ’free-water clause’, which permitted vessels in the docks to unload directly into lighters and thereby avoid paying the dock company’s dues. Another was the increasing size of ships, and so the repeated need to rebuild the entrances. The 1870s was a decade of prosperity for the docks, but this was soon reversed. The dock company sought to revive its declining profitability by constructing new docks downriver at Tilbury. These were completed in 1886, but at a cost which far exceeded the estimate, and with little initial success in attracting traffic. The company therefore reduced its charges, breaking the existing cartel and inaugurating a competitive battle among the dock companies on the Thames.

These problems affected the funding of local government: to help it through this difficult financial period, the dock company negotiated a reduction in its rates, and in 1891 was paying only 58 per cent of its 1839 level. But there was increasing pressure on the rateable income at a time of high unemployment, and the level of rates had to be raised, making Poplar one of the highest-rated parts of London. In 1906–7 the combined rates were 11s 8d in the pound, the highest in the capital, although in a more prosperous area such as Kensington they were only 6s 8d. Throughout the 1890s and 1900s only two or three areas in London charged a higher level of rates than Poplar. High rates deterred new business, and retailers found it increasingly difficult to continue trading in the area. The failure of Randall’s Market, in the north of the parish, to establish itself as a shopping development, and the removal of retailers from Poplar High Street as Chrisp Street developed as a shopping street, were symptomatic of the problems of the local business community.

The dispirited appearance that the High Street presented at the turn of the century epitomized Poplar’s identity as one of the poorest and most depressing parts of the capital. In 1887 almost 40 per cent of the population of the parish was classified as living ’below the poverty line’, compared with 30 per cent for the capital as a whole. At the same date fewer than 6 per cent of the inhabitants were adjudged to be middle class, the figure for London being almost 18 per cent. From the seventeenth century, the merchants and shipbuilders with interests in Poplar had favoured Essex as a place to live, and the area was not wealthy enough to attract or retain more than a few members of the professions.

Figure 2:

Poplar, Blackwall and the Isle of Dogs. Land-use plan c1913

Poplar’s reputation as a deprived part of the capital attracted the attention of missionaries, social investigators and members of the literati, whose characterizations created an impression of a district of ’dreary, slummy streets’ that were ’narrow, ugly and dirty,’ containing ’uniform rows of two storey cottages in grey brick’ that were no better than ’miserable hovels’. The general impression was one of ’dreariness and drabness of the heart-breaking kind’. Even the state of the roads attracted adverse comment. One visitor to the Isle of Dogs was appalled at their condition, which made it difficult to realise that ’Cubitt Town and Millwall are after all integral parts of a Metropolitan borough and are within the area governed by the London County Council’.

Poplar also attracted attention because of the development of a radical political element, concerned to address the effects of poverty and unemployment. From this background emerged two figures of national importance: Will Crooks (1852–1921) and George Lansbury (1859– 1940). Both served as Mayor of the Borough of Poplar (created in 1900), sat on the LCC, and were Labour MPs, Lansbury being leader of the party between 1931 and 1935.

Crooks also served as Chairman of the Poplar Board of Guardians, reforming the administration of the workhouse, one of the largest in London. Attention was drawn to the Board’s poor-relief policies when economic recession produced high numbers of unemployed, as in 1903–6, 1908–9 and the 1920s. It was the levels of assistance paid to those receiving outdoor relief which attracted particular attention. In April 1922, those drawing relief accounted for 18 per cent of the borough’s inhabitants. As one of London’s poorest boroughs, Poplar was concerned to alter the existing rate system in the capital. In the absence of a subsidy from outside, a poor borough such as Poplar, with low rateable values, had to levy a high level of rates to obtain the sums required for poor relief. For example, in 1921 a rate of 1d in the pound produced £31,719 in Westminster, but Poplar Borough Council had to levy a rate of 83 4d to obtain that sum. It was alleged that the achievement of rate equalization among the London Boroughs, by which they would pool their resources, was the motive behind the high levels of outdoor relief paid by the Guardians in 1903–6, and it had become their avowed policy by 1921. The Borough Councillors brought matters to a head in 1921, when they chose to levy only the rates for the Borough and Board of Guardians, refusing to meet the precepts from the LCC and Metropolitan Asylums Board. This led to the imprisonment of 30 Councillors, including Lansbury, for contempt of court, and attracted widespread publicity. From November 1921 the costs of outdoor relief were met through the Metropolitan Common Poor Fund, with the poor rate being assessed on the whole County of London, rather than by each Metropolitan Borough individually.

The term ’Poplarism’ was coined in November 1922 by the Glasgow Herald, although the policies to which it referred had been applied in Poplar since the early 1900s. Poplarism was defined as ’the policy of giving out-relief on a generous or extravagant scale, practised by the Board of Guardians of Poplar about 1919 or later; any similar policy which lays a heavy burden on rate-payers’. In the 1950s this harsh definition was revised to read: ’The policy of giving generous or (as was alleged) extravagant outdoor relief, like that practised by the Board of Guardians of Poplar in 1919 or later’. The word remained current during the 1920s and 1930s as a generic term used disparagingly with reference to local authorities governed by the Labour Party. George Lansbury’s riposte was that Poplarism meant ’efficient, cheap public administration’.

The radicalism of the early decades of the twentieth century was an expression of localism, reflecting an awareness of the needs of the local community, rather than the wider issues within London. Yet much of Poplar’s experience in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was similar to that of the other parts of London’s East End riverside. Some of the characteristics of the East End that can be identified in Poplar are the relatively high level of poverty, poor housing, lack of infrastructure and shops, and failure to attract commercial and professional middle-class groups.

Like other dock areas, Poplar contained a number of immigrant communities. Those from India and the East Indies reflected its long-standing connections with both regions. According to a former Bishop of Stepney, in 1881 ’the Oriental was a familiar figure in the East India Road. A string of lithe and loose-limbed Indians, ready to sell you an inlaid walking stick; or a group of Chinamen in native dress; or a big and coal-black Nubian would meet you … But now Football Club was formed, and on match days the line carried large numbers of supporters. However, in 1902 the Greenwich ferry was withdrawn when the foot tunnel opened, and in 1910 the football club moved to New Cross, south of the river.

By then the London and Blackwall and the North London had also seen a dramatic diminution in their passenger trade. The expansion of other railways north and south of the Thames, together with the opening of new dock systems downstream from Poplar, led to a drastic decline of river traffic from Brunswick Wharf during the second half of the nineteenth century. From 1883 Sunday services on the London and Blackwall were reduced, and from 1890 passenger trains on the North London ceased to run to Blackwall and terminated instead at Poplar Station. The general introduction of telephones in offices during the 1890s and early 1900s dealt another blow to the London and Blackwall, which was much used by messengers operating between the City shipping offices and ships at the docks. Then both the London and Blackwall and the North London Railway suffered from competition from the electric trams, particularly when they began to run from Aldgate to Poplar in December 1906, forcing the former to reduce its services.

During the First World War passenger services on the London and Blackwall and the Millwall Extension Railway were again reduced, and after the war there was increasing competition from motor-buses. Passenger services on the two lines ceased in 1926 and the Millwall Extension was completely abandoned between Glengall Road and North Greenwich. In the later 1920s the PLA constructed a new entrance to the South Dock of the West India Docks from Blackwall Reach, severing the remaining central part of the Millwall line. In order to maintain a rail connection with the Millwall Docks, a diversion line around their west side was built by the PLA and opened in January 1929. Poplar lost its sole remaining passenger rail-link when the passenger service on the North London line between Dalston Junction and Poplar was withdrawn in May 1944.

After the Second World War shipment of goods to and from the docks was increasingly by road, so that by 1960 only 14 per cent of exports were arriving by rail, compared with 41 per cent in 1937. Most of the goods lines and depots in Poplar, Blackwall and the Isle of Dogs were abandoned during the 1960s, and railway operations by the PLA in the Millwall and West India Docks ceased in 1970. However, goods traffic to Poplar Dock (the former North London Railway dock) continued until 1981.

Thus, by the time that the LDDC came into being railway activity had virtually ceased in Poplar and the Isle of Dogs. The isolation of the area and its inaccessibility from central London, made worse by the fact that the Underground system never reached there, was a serious hindrance to the redevelopment prospects of the docks. Plans to extend the Jubilee underground line were shelved by the government in 1980 because of the cost, and London Transport, in association with the LDDC and the Greater London Council, decided to go ahead with a light railway, which could be built relatively cheaply and quickly. The Docklands Light Railway (DLR) opened in 1987, with routes from Tower Hill (’Tower Gateway’), on the edge of the City, and Stratford to the east converging just north of West India Quay station, and then running through the heart of the Isle of Dogs Enterprise Zone to the southern terminus at Island Gardens (see plan C). Approximately two-thirds of the DLR was built on disused or under-used railway lines. East of Limehouse station it is carried on a former London and Blackwall Railway viaduct, and at the south end of the Isle of Dogs on a viaduct built for the Millwall Extension Railway. The Poplar–Stratford line follows much of the route of the North London Railway. An extension of the DLR to Bank station, in the heart of the City, opened in 1991, and an extension eastwards to Beckton in 1994.

The development of Canary Wharf led to a revival of plans to extend the Jubilee line, and work on a ten-mile extension, from Green Park, via Waterloo and London Bridge to Canary Wharf and Stratford, began in late 1993. When it is completed, the Isle of Dogs will have better rail communications with central London than ever before.

Administrative History

The parish of All Saints, Poplar, was created in 1817 by an Act of Parliament. It succeeded the hamlet of Poplar and Blackwall, one of the constituent hamlets of the parish of St Dunstan’s, Stepney, taking over its boundaries unchanged. The hamlet contained 1,158 acres, comprising Poplar, Blackwall, and the Isle of Dogs.

Poplar and Blackwall was administered in the same way as the other hamlets which made up the very extensive parish of St Dunstan’s. It contributed a proportion of the parish’s vestrymen and officers, and a share of the rates. It also had its own administrative structure, which consisted of a churchwarden, two overseers, a constable and a number of other officers, all of whom were chosen at the Meetings of the Inhabitants, a body of ratepayers which had the power to levy a separate rate for disbursement within the hamlet.

The size of St Dunstan’s vestry fluctuated, as some hamlets separated from it to form independent parishes and new ones were created in response to population growth (fig. 4). Poplar and Blackwall was considered as a potential parish on several occasions between 1650, when separation from St Dunstan’s was recommended in a report produced by Parliament’s surveyors of church lands, and the creation of St Matthew’s, Bethnal Green, in 1743, which marked the end of the process of parish creation in London until Poplar achieved independence in 1817. The closest that the hamlet came to achieving separation followed the establishment of the Commission for Building Fifty New Churches in 1711, and by a scheme devised by the Commissioners in 1727. With the completion of Poplar Chapel in 1654, the hamlet had a building which could readily be adapted as a parish church. On the other hand, it was a relatively poor hamlet, and it had a comparatively small population of only 2,250 in the early eighteenth century, well below the notional figure of 4,750 for each new parish upon which the scheme for the Act of 1711, which established the Commission, was based.

A further problem was the uncertainty over the right of presentation of the minister, for although the East India Company had come to act as patron, on the basis of its contribution to the minister’s stipend, the legality of its claim was uncertain and led to disputes with the inhabitants when they were presumptuous enough to attempt to nominate their own candidate. This doubtful situation was further complicated when the advowson of Stepney parish was purchased by Brasenose College, Oxford, in 1710, for it thereby acquired the right to nominate the minister of the Chapel. The Company reacted by negotiating with the college for permission to make every third nomination, and in practice it was the Company which continued to present the minister (the college later claimed to have acquiesced in the arrangement because it did not itself have the means to provide a stipend). The ratepayers’ limited abilities regarding the maintenance of the minister were further weakened because holders of ground in the Isle of Dogs were exempt from contributing towards that cost, an arrangement that presumably originated during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, when there was a chapel on the Island.

The hamlet’s administration came under increasing pressure following the construction of the West India and East India Docks and the City Canal in the first decade of the nineteenth century, which produced a larger population and greater numbers of poor. The workhouse became increasingly inadequate to hold the numbers of paupers requiring indoor relief. On the other hand, extra revenue was available from the rates paid by the dock companies, and by the City Corporation, as proprietors of the canal.

The administrative arrangements were still based upon the Bishop of London’s Faculty of 1662 regulating the Stepney vestry, and in 1813 the leading inhabitants, perhaps conscious of the weakness of their position, obtained an Improvement Act placing the administration of the hamlet on a more secure footing. The terms of the Act related chiefly to the power to levy rates and make contracts, the administration of the property of the hamlet and the workhouse, poor relief, the maintenance of the highways and sanitary arrangements. The two dock companies and the City Corporation were allotted a total of 58 nominated places on the body of Trustees, who were empowered to implement the terms of the Act, and the chairman and secretary of the East India Company were also entitled to serve as Trustees. The largest number of Trustees came from amongst the residents of the hamlet, for at least 150 residents either rented property worth £30 per annum or were assessed at £18 or more per annum for the poor rate and thereby qualified to act as Trustees, and a further 10 nonqualifiers were chosen annually by the inhabitants. Because of the continued growth of population and rising property values, the numbers of Trustees increased, from c220 at the passing of the Act in 1813 to c450 by the 1850s.

Figure 4:

Outline plan showing the sub-division of the ancient parish of St Dunstan’s, Stepney, into independent parishes – from the separation of St Mary’s, Whitechapel, in 1338 to the creation of All Saints’, Poplar, in 1817 — together with the adjoining parish of St Leonard’s, Bromley

With the administration of the hamlet more securely established and the number of potential communicants having far outstripped the accommodation available in the Chapel, it was a logical step for the inhabitants to seek full parochial status. The problems which had arisen a century earlier were not now insurmountable and the various interests were reconciled, with comparatively little difficulty. Brasenose’s rights to the advowson were acknowledged, the rector, clerk and sexton of Stepney were compensated for their financial losses and the agreements of the Bishop of London, the East India Company and the East India and West India dock companies were obtained. By an Act of Parliament of 1817 the hamlet was replaced by the parish of All Saints, Poplar. The Act established a vestry, with identical qualifications to those applicable to the body of Trustees, and the other trappings of parochial administration. It also made provision for the appointment of a rector and a lecturer, and for the erection of a church and a rectory.

The Trustees’ administrative functions were eroded by Peel’s Act of 1829 which created a police force in London and thereby removed their role of watching the streets, and the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1837, which transferred responsibility for poor relief to the Board of Guardians of the newly formed Poplar Union, consisting of All Saints’, St Leonard’s, Bromley, and St Mary’s, Stratford Bow. The Trustees opposed the Union, partly because it combined Poplar, which was a riverside parish, with two parishes to the north without frontages on the Thames, and which were less densely populated, in 1841 having only a half of the population of Poplar.

Despite those objections, the same combination of parishes was adopted for the Poplar District Board of Works, created by the Metropolis Local Management Act of 1855. This provoked even fiercer resistance from the Trustees, both on the grounds of the incorporation of Poplar with Bromley and Bow, and the imposition of a more restricted franchise in the election of the members of the District Board than that which applied in the choice of Trustees. Furthermore, although Poplar still had an absolute majority on the Board of Guardians, the 1855 proposals allotted it only one half of the members of the District Board. It was argued that Poplar’s size and rateable value were sufficient for the parish to retain a separate status within the terms of the Act, but the point was not conceded.

The Act of 1855 removed from the Trustees their responsibility for paving, drainage, lighting and other functions comprised under the general heading of ’improving’, yet the Improvement Act remained in force. Their authority thereafter was essentially the power to make and collect the rates, the upkeep of their property and the appointment of various officers.

The Metropolis Local Management Act of 1855 established a new vestry in Poplar, empowered to elect the parish’s 24 members of the District Board of Works. It also took over the electoral functions of the existing vestry and Meeting of Inhabitants in respect of the choice of parish officers and the ten co-opted Trustees. Its other duties were chiefly concerned with certain powers regarding the highways and the management of the public baths and library. The parish vestry established in 1817 remained in being, shorn of many of its original functions and now concerned only with such parochial affairs as the church rate, the appointment of organist, lecturer and vestry clerk, the election of one of the churchwardens – the other was nominated by the rector – and maintenance of the rectory.

When the Metropolitan Board of Works was replaced by the London County Council in 1889 the District Boards and Metropolis Local Management Vestries continued unaltered, but they were abolished in 1900 by the terms of the London Government Act of the previous year. The boroughs created by that Act included the Metropolitan Borough of Poplar, which covered virtually the same area as the District Board of Works had done. The 1899 Act rendered obsolete the residual powers held by the Trustees under the Improvement Act of 1813, and that Act was duly repealed in 1901, but did not affect the compulsory church rate (which was ’probably the last rate of the kind in the Metropolis’) and that was abolished by a separate Act in 1903. Poplar contained 35 per cent of the population and 44 per cent of the gross rateable value within the new borough, and its five electoral wards contributed 15 of the 42 members of the Borough Council (there were also seven co-opted aldermen). Anomalies between the three constituent parishes in such matters as the levying of the rates created some difficulties, and so in 1907 a new civil parish of Poplar Borough was created by the merger of All Saints’, St Leonard’s, Bromley, and St Mary’s, Stratford Bow.

In 1963 the London Government Act combined the Metropolitan Boroughs of Poplar, Stepney and Bethnal Green into the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, covering a large part of the area occupied by the medieval manor of Stepney. This was one of the 32 Borough Councils created by the Act, which also replaced the London County Council with the Greater London Council and the Inner London Education Authority, in turn abolished in 1986 and 1990 respectively.

The ward divisions within Tower Hamlets continued to employ the former western boundary of All Saints’, between the Limehouse Cut and the Thames, with a few minor modifications, but the remainder of the line of the parish boundary was altered. The East India Dock Road, between the Lea and the boundary with Limehouse, formed the northern boundary of a ward which was designated as Poplar South until 1978, when it was renamed Blackwall. A boundary drawn across the Isle of Dogs passing through the South Dock of the West India Docks divided this ward from Millwall. The two wards of Poplar West and Poplar East to the north of the East India Dock Road incorporated parts of All Saints’. In 1978 they were renamed Lansbury and East India respectively, and the former was slightly enlarged by the addition of an area to its south-west which extended its boundary beyond that of the former Borough of Poplar. In 1987 Blackwall and Millwall wards were combined into the neighbourhood of the Isle of Dogs as one of the seven such areas established within the borough.

As a result of the 1978 changes the name ’Poplar’ was no longer applied to an area of civil administration. The neighbourhood arrangements in force between 1987 and 1994 revived it for a neighbourhood consisting of four wards lying entirely to the north of East India Dock Road, and so, ironically, not including the area of the hamlet of Poplar around the High Street, which was placed within the Isle of Dogs neighbourhood.

Modern Docklands and the London Docklands Development Corporation

The GLC purchased St Katharine’s Dock from the Port of London Authority in 1968 and held an open competition for its development (won by Taylor Woodrow), but its Greater London Development Plan of 1969 failed to foresee the closure of the remainder of London’s enclosed docks, and concentrated on plans for regenerating riverfront sites throughout London. In 1970 the closure of the London Docks and the Surrey Docks prompted the GLC to consider drawing up strategic plans for the redevelopment of riverside areas east of the Tower, as far as Gravesend and Tilbury. As a first stage, it organized a conference of the various borough and county councils involved, as well as the PLA. In 1971 the Government and the GLC jointly commissioned outside consultants to prepare a Docklands feasibility study, which was published in 1973. In January 1974 the Docklands Joint Committee was set up to take responsibility for planning (development control, strategic plans, and consultation papers) and implementing the redevelopment of London Docklands. It comprised representatives of the GLC and Greenwich, Lewisham, Newham, Southwark, and Tower Hamlets Borough Councils. In 1976 the Joint Committee issued the London Docklands Strategic Plan, the basic aim of which was

’to use the opportunity provided by large areas of London’s Dockland becoming available for development to redress the housing, social, environmental, employment/economic and communications deficiencies of the Docklands area and partner boroughs and thereby to provide the freedom for similar improvements throughout East and Inner London.’

The Plan required £1,138 million of public investment to be matched by £600 million of private money, yet it offered no real idea of how the latter would be raised.

The South East Economic Planning Council, an independent body which advised the government, urged in response to the 1976 Strategic Plan – the setting up of a development corporation, which would be free of political intervention and would be more likely to win the confidence of developers and investors. Such a suggestion was not acceptable to the Labour Government of the day, and Docklands was left to the local authorities, who adopted their normal approach of wide public consultation and much discussion between the different councils and other interested organizations. Progress was inevitably slow, and in 1981 the Conservative Government, seeking to accelerate redevelopment, vested control of the Docklands area, including the Isle of Dogs, in the London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC), one of the first two Urban Development Corporations (modelled, as suggested, on those of the New Towns) to be set up as a result of the Local Government and Planning Act of 1980 According to the Act, the object of the Corporation would be

’to secure … regeneration … by bringing land and buildings into effective use, encouraging the development of existing and new industry and commerce, creating an attractive environment and ensuring that housing and social facilities are available to encourage people to live and work in the area.’

The LDDC was given powers to acquire and dispose of land, as well as responsibility for all planning matters in the Docklands area (see plan C). Enjoying strong government support, the Corporation was not subject to the financial constraints then imposed on local authorities, and did not answer to an electorate.

The East India Dock Road was taken as the northern boundary of the Corporation within Poplar, and so only the Lansbury Estate section of the historic parish of All Saints is excluded from its jurisdiction. In a move which was to have major repercussions for the redevelopment of part of the parish, in 1982 the government designated much of the old docks area on the Isle of Dogs as an Enterprise Zone. This status offered tempting financial incentives to commercial developers and much easier planning processes. The result has been a whirlwind of development producing a physical transformation that has been rapid and spectacular. What is not yet clear is the lasting effect this will have on the economic and social life of the area.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s attention on the Docklands area largely focused on the Enterprise Zone of the Isle of Dogs. The term Docklands also became synonymous with prosperity: the high levels of investment and property prices in particular attracted nationwide comment. Canary Wharf was the most striking and controversial development of the period and completely transformed the scale and rate of change in the area. Yet the new commercial developments and housing are only the most recent of the succession of changes that has produced the environment of late-twentieth-century Poplar. The construction and enlargement of the docks, the piecemeal development, fragmentation and decline of the industrial sites, and the building of the nineteenthcentury houses and their twentieth-century replacements, have all been major elements in the creation of an area which is both fascinating and challenging in its complexity.