| Kensington Park | Notting Hill in Bygone Days by Florence Gladstone |

Bayswater end |

Before describing the streets to the east of the Hippodrome Estate, connecting Notting Hill with Bayswater and Paddington, it will be best to consider the growth of the district which has had such a disastrous effect on the development of the western borders of Kensington Park. The name now in use has been given to this chapter, but the area to be described was originally known as Kensington Potteries and Norland Town. Already it has been told how a company of pig-keepers established themselves in the early years of the nineteenth century among the brickfields at the foot of the hill.

By 1840 the little colony was an irregular group of hovels, which were more and more taking the form of a self-contained village. There were two main streets, James Street and Thomas Street.’ James Street was a portion of the old ” public road,” now included in Walmer Road. Thomas Street later on became Tobin Street. Notting Dale, a charming name were it not for its associations, at first was a small turning, apparently identical with Thresher’s Buildings. This alley of low houses, with good back-yards, was described in 1904 as ” a double row of cottages with a paved way between them that seem to have been lifted bodily out of a Yorkshire mill town and dropped with their quaint outhouses on the confines of Kensington.”

Very little of the primeval hamlet remains, though Heathfield Street and Mary Place and Hesketh Place, formerly known as Sidney Place, still have tiny front gardens and stabling with tiled roofs ; forming a curious little oasis in the midst of a London slum. The ” Black Boy ” and the ” King’s Arms ” were the names of notorious public houses off James Street. By the side of the Kiln, which has been preserved as an historical relic, was a range of sheds, and ” Potteries ” belonging to Mr. Adams also occupied the west side of Pottery Lane, where is now Avondale Park. Mary Place (dedicated not to Our Lady but to a Mary who kept pigs) ended in Mr. Stephen Bird’s brickfield, and the row of Bird’s cottages, close to the site of Sirdar Road L.C.C. School. Brick-making was carried on chiefly during the five summer months, and the men worked fifteen or sixteen hours a day and for some hours on Sunday.

The wives and elder children often helped in the work ; indeed children worked the same long hours as their fathers, carrying loads of wet clay on their heads, and looking like pillars of clay themselves ; until, through the efforts of Lord Shaftesbury, this form of child-slavery was abolished by Act of Parliament. A family party could earn large wages for those times : even £2 to £3 a week. But the work was very exhausting, and the men considered it necessary to drink at least seven pints of beer a day.

Naturally this kind of life reacted on home conditions, and in winter a brick-maker’s family might be penniless. At this period, however, drunkenness was almost unknown among the women. The Sunday amusements were cock-fighting and bull-baiting. Many dogs were kept for dog-fights and rat-killing. Neighbours were afraid of these dogs. Even the inhabitants did not venture out after dark, for, besides the dogs, there were the dangers of the unmade roads. Meanwhile the pigs kept had grown in numbers ; until at one time, on the eight or nine acres of the district, there were 3,000 pigs and 1,000 human beings, living in some 260 hovels. With the increase of population sanitary conditions had become more and more unsatisfactory. An official report of the year 1849 states : ” The majority of the houses are of a most wretched class, many being mere hovels in a ruinous condition, and are generally densely populated. They are filthy in the extreme and contain vast accumulations of garbage and offal. . . . On the north, cast and west sides this locality is skirted by open ditches of the most foul and pestilential character, filled with the accumulation from the extensive piggeries attached to most of the houses.”

Besides these open sewers fetid pools formed on the surface ; one sheet of water, known as the ” Ocean ” being nearly an acre in extent. The water in the wells was black, even the paint on the window frames was discoloured by the action of sulphuretted hydrogen gas. The inhabitants all looked unhealthy, with sunken eyes and shrivelled skin, the women especially complaining of sickness and want of appetite. It is hardly to be wondered at that ” nobody ever cared to come nigh the place.”

At last, in the early forties, a small school was opened through the exertions of Lady Mary Fox, of Little Holland House, and another friend of the district presented the site for St. James’s National School. But the first centre for directly religious work was started by combined members of Silver Street Baptist and Hornton Street Congregational Chapels. For several years services were held and schools carried on in a house with unplastered walls, the precursor of Notting Dale Chapel and school in Walmer Road. This little Mission-room in the Potteries can claim to be the earliest place of worship in the whole area of North Kensington.

By the middle of 1845 the churches of St. John’s-on-the-Hill, and St. James’s Norlands were established. And in 1847 the London City Mission sent one of their missionaries to the district.

Such was the state of affairs when, in the summer of 1849, London was visited by cholera. As was to be expected Kensington Potteries suffered severely from the epidemic. Then the infection spread to more comfortable homes. Between September 11 and 22, 1849, seven deaths occurred ” in Crafton Terrace a quarter of a mile away.” This was probably Crafter Terrace on Latimer Road.

The attention of the public was drawn to the locality through these deaths, and Charles Dickens brought it into further notice by an article which appeared in one of the first numbers of House-hold Words. This article begins : ” In a neighbour-hood studded thickly with elegant villas and mansions, viz.: Bayswater and Notting Hill, in the parish of Kensington, is a plague-spot, scarcely equalled for its insalubrity by any other in London ; it is called the Potteries.” These disclosures led to discussions both in and out of Parliament. As a result ” a good road was made,” no doubt Princes Road, and supplies of fresh water were introduced. But the drainage of the area was found to be a difficult problem on account of the low level of the ground. Seven years later the Medical Officer of Health had to give a still worse account of the conditions of ” one of the most deplorable spots not only in Kensington but in the whole Metropolis.” The ground was still saturated by drainage from the badly paved styes of over 1,000 pigs, and all the wells were contaminated. Many of the houses were in a very dilapidated state, and old railway carriages and worn-out travelling vans might be seen converted into dwellings.

The death-rate in 1856 was actually 40 to 60 per 1,000, and 87. 5, or 43 out of every 50 deaths, were of children under five years of age. Smallpox was reputed to be ten times more fatal than in the surrounding districts. This statement is valuable in view of the heavy toll of life in subsequent epidemics. Not only was this the case in the outbreaks of cholera in 1849 and in 1853, when the Vicar of St. John’s lost his life, but in the bad attack of scarlet fever which occurred about 1870, and the devastating wave of influenza in 1889-1890. After the report of the Medical Officer in 1856 ” great efforts were made to get rid of the swinish multitude altogether, but the shrewd chimney-sweep, Lake, seems to have foreseen this evil day, and ‘ for the purposes of pig-keeping ‘ had been inserted in the very leases which the people were able to produce. • . . Nothing but a special Act of Parliament could remedy the existing evil.”

In the middle years of the nineteenth century a wide-spread interest was felt in questions relating to the welfare of the poorer sections of society, and several fresh methods of philanthropy were introduced. Two of these new methods came into being in this ” frowsy suburb.” And in the story of the establishment of the first Mothers’ Meeting, and the earliest Workmen’s Institute, graphic pictures are given of the early development of Notting Dale.,* It was at the suggestion of Mr. Parfitt, the City Missionary, that Mrs. Bayly undertook the manage-ment of the ” Mothers’ Society.”

This met for the first time on the evening of Monday, November 3, 1853, and it is remarkable how closely hundreds of Mothers’ Meetings to-day conform to the scheme evolved nearly seventy years ago. When the numbers in attendance became on an average eighty to one hundred some of the women were formed into another group. By 1863 there were three Meetings in the neighbourhood under the management of one Ladies’ Committee, besides a similar Meeting connected with St. James’s Church, conducted by the daughter of Sir Edward Ryan in Phoenix Place off Queensdale Road. Until a trained Bible-woman was obtained by the help of Mrs. Ranyard in 1860, Mrs. Trickett acted as ” Female Missionary.” Her name is known in the locality through the wood-chopping business inaugurated by her son. Mrs. Swindler, in 1915, told the writer that, when she was a young married woman living in Princes Road, she used to go on a Monday afternoon to Mrs. Bayly’s ” little chapel,” which was behind the present police station in Sirdar Road.

This was on the outskirts of the Potteries’ village, and fields reached almost to the door. Allotments and small market-gardens lay all around, and a narrow stream on the north side of St. Katherine’s Road, now Wilsham Street, had to be crossed in order to reach the Mothers’ Meeting. Mrs. Swindler’s little son used to take crusts to feed the baby pigs and the geese met with on the way. The ” Piggeries and Potteries ” (a name said to have been invented by the Rev. Charles Spurgeon) were not confined to the eight or nine acres of the original estate, but had spread both to the south and to the west. St. James’s parochial schools were surrounded by pig-sties in 1859, and the health of the Rev. R. N. Buckmaster, who nobly worked as curate from 1847 until after 1871, suffered severely owing to ” exposure to so much damp, and the stench of the highways and byways.”

Here the Norland and Potteries Ragged School was opened by Lord Shaftesbury in 1858. (The work is still carried on in the same building under the name of the Holland Park Mission, St. James’s Place.) The building of the Birmingham, Bristol and Thames Junction Railway (The West London Railway) has already been mentioned. After that line was built about the year 1836, a track ran across the fields from Mortimer Terrace, now called Boundary Road, to the archway leading to Wormwood Scrubbs.

This track, afterwards Latimer Road, followed the course of the ” rivulet ” ; the actual boundary at this time being an open ditch which was crossed by plank bridges when houses were built on the east side of the road. Allotment grounds lay at the south end of this track or footpath ; and it was not until about 1860 that Norland Road North was made across these allotments to connect Latimer Road with Shepherd’s Bush.

The ” Old Inhabitant ” describing the state of affairs in the middle forties writes : ” Beyond the Colony of pig-keepers at the end of Pottery Lane I discovered another in Latimer Road. . . . But what a place it was when 1 first discovered it—comparatively out of the world—a rough road cut across the fields the only approach. Brick-fields and pits on either side, making it dangerous to leave on dark nights. A safe place for many people who did not wish everybody to know what they were doing.” In this desolate region the worthy man conducted services and established a day school. Unfortunately the position of this school, as well as the identity of the Old Inhabitant has, so far, eluded discovery.

Latimer Road owes its name to Edward Latymer, Esq., citizen and feltmonger, son of a Dean of Peter-borough, who, at his death in 1626, bequeathed thirty-five acres of field land north of Shepherd’s Bush, with further property in Hammersmith, for the support of six poor men and the education of eight poor boys in the Charity School which he had founded in 1624. The charity was added to in later years and now provides for many pensioners and hundreds of day scholars in the two Latymer Foundation Schools. A small portion of the estate lies within the parish of Kensington, and the benefits of the charity are devoted indiscriminately to children from both parishes, but the quaint provisions as to clothing and education are no longer required of the recipients of the bounty.6 The ” Latymer Arms ” at the corner of Boundary Road was within living memory a one-storied country inn. The quartered arms of Latymer and Wolverton appear on the present tavern, the property having descended to Latymer through his great-grandmother, Elizabeth Wolverton. It must have been about the time when the ” Old Inhabitant ” came into the district that Mr. James Whitchurch, an attorney of West Southampton, then known as Blechynden, bought fifty acres of land in Hammersmith and Kensington, at the rate, it is said, of £10 an acre.

The ” Fifty Acre Estate ” abutted on the Latymer Estate, joined the property of Mr. Stephen Bird, the owner of large brick-fields, and spread some distance to the north. In this northern portion an outlying group of roads was projected shortly after 1846. These roads included part of Lancaster Road, Silchester Road and Bromley, now Bramley Road, and were bounded by the upper end of Walmer Road, which followed the curved line of the Hippodrome pallisade. Countrified houses with dilapidated gardens, used as drying grounds for linen, may still be found in these roads, but several of these early houses were demolished to make way for the Kensington Baths and Wash-houses. Mr. Whitchurch built for his own use a house in Lancaster Road, now No. 133, but he died near Blechynden. He was not exactly an accommodating landlord, and he was fully acquainted with ” his rights and remedies,” but he insisted on having wide roads across his property, and the generous proportions of Latimer Road, and the roads already mentioned, have since proved of inestimable benefit.

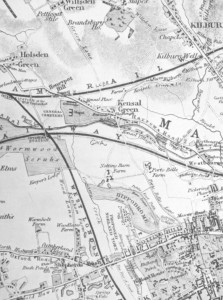

The map of 1850 shows various buildings along Latymer, now Latimer Road. The more respectable residents had pig-sties in their back yards, the rougher element in many cases inhabited mere hovels, where the family and their animals, pigs, horses, dogs and poultry, lived together in ” squalid degradation.” The final eviction of pigs by order of the Vestry of Hammersmith was not carried out until 1883. For many a year this action was much resented in the locality.

Already gipsy vans were accustomed to make their appearance each autumn, to disappear again at the beginning of the following summer. The gipsies established themselves at the south end of Latymer Road, and half a mile further to the north where St. Helen’s schools have been built. The dark coloured tents or ” tans ” were also pitched on Black Hill, now included in Avondale Park, but their chief encampment was on the low ground where St. Clement’s Church was afterwards placed. This land had formerly been part of Bird’s brick-field. In 1862 the gipsies of Latymer Road were reckoned at from forty to fifty families. The following incident illustrates the curious conditions which prevailed. Mr. Moore was the owner of a small farm on the west side of Latymer Road. One evening a young gipsy woman, whose tent was pitched on Mr. Moore’s ground, came to him in distress, saying that a strange man must have got into her tent, for she could hear him snoring. On accompanying her, Mr. Moore discovered that the intruder was, not a man but, an old asthmatic sow of his own, which had strayed, and had found a soft corner in the gipsy’s bed. The patriarch of the tribe, known as ” the King of the Gipsies,” was a picturesque old man with the regular gipsy name of Hearn. He had fought through the Napoleonic Wars, and had wandered all over the country “chair-bottoming.” In the early sixties, when more than ninety years of age, he settled down and made himself a little home out of an old advertising van with a tin pail for a chimney. It was at this time that mission work started among these gipsies. ” Old Hearn ” signed the pledge, and many other ” travellers ” gave up drunkenness and swearing and even abandoned the lucrative practice of fortune-telling. They sold their horses, which formerly had been fed at the expense of the public, took out hawkers’ licences and, for reasons known to themselves, discarded the Romany language. Besides this some thirty-five couples went through the marriage service. The well-known evangelistic work of ” Gipsy Smith ” and his family is an outcome of this revival. A gipsy tea-meeting was a sight not easily to be forgotten. The writer can recall how, during the meeting that followed tea, a crying baby was hailed with joy, as it formed an excuse for a man to get up from the unaccustomed hard seat and pace the room with the child in his arms. At last a tent, to be used for religious and educational purposes, was pitched among the dark ” tans.” This tent was opened on a sultry afternoon in the summer of 1869. But it could not be used for long, as an outbreak of scarlet-fever occurred, and the local authorities insisted on the abandonment of the gipsy camps. Ever since 187o the gipsies in Notting Dale have ostensibly lived under roofs ; but many an inhabited van has been hidden away in back premises. Although a good deal of intermarriage with the ordinary population has taken place, beautiful dark-eyed children with massive hair may still be found in the elementary schools. Pictures of the gipsies of Latymer Road, appeared in the Illustrated London News in 1879, and Mr. G. R. Sims, writing in 1904, tells of a genuine Romany funeral which had recently occurred.

Meanwhile in Kensington Potteries and Norland Town conditions had changed. When Mr. Goderich, M.O.H., made his report in 1856 men belonging to the building trades and other casual labourers had come to live in the district ; the number of pigs had declined, and many of those were fattened on commission instead of being owned by the pig-keepers. The winter of 1856 was one of unusual distress. Little unskilled work was to be obtained, and ” had it not been that many of the women found employment as charwomen and laundresses, numbers of families would have had no resource but the workhouse.” Through this simple and apparently praiseworthy action on the part of the women a trade was introduced which in time became the chief industry of Notting Hill, ousting the brickmakers and pig-masters.

At first, no doubt, a woman would take in washing from a family in one of the better-class houses, and the clothes would be dried in her garden. But later on small laundries, owned and managed by a man and his wife who employed about half-a-dozen women, became a distinguishing feature of the locality. In the absence from home of a woman worker her baby had to be left to the care of a neighbour, often an old woman in a back kitchen, the other children ran wild or were locked in till the mother returned at night, when she tried to carry out her domestic duties after twelve hours at the wash-tub or the ironing board. Standing in the atmosphere of steam frequently produces varicose veins and rheumatism. It is not surprising, therefore, that many of these poor women resorted to stimulants, with the natural result of more miserable homes and less healthy children. As the women became the principal wage-earners the district more and more was ” infested with a contemptible set of men . . . loafers or worse,” and it is well recognized amongst the poor that men move to North Kensington ” for the purpose of being kept by their wives.” There is a local saying that ” To marry an ironer is as good as a fortune.” Those who best know the laundry workers will acknowledge the many brave souls amongst them, but women’s work away from home inevitably has a demoralizing effect. These evils were of slow growth. The women were still a sober race when, in 1859, a crusade against the drinking habits of the men was determined on. A ” Rescue Society,” afterwards known as the Temperance Society, was formed, the working-men members being organized as district visitors to their mates. It soon became clear that, if rough men were to be saved from drink, they must have some place where they could meet without being exposed to temptation. Mechanics’ Institutes had already been founded : a public-house without drink seems to have been quite a new venture. After some delay two skeleton houses were purchased in Portland Road, and were adapted for the purpose. A model of the Eddystone Lighthouse was fixed outside the building, and showed its light along the three roads converging on the spot. The ” Workmen’s Hall ” was opened on March 12, 1861, by Dr. Tait, Bishop of London, and was subsequently managed by a committee of men presided over by Captain and Mrs. Bayly. By the end of 1862 there were six or seven hundred staunch teetotalers on the roll. The original Work-men’s Hall was closed in 1866 owing to unforeseen difficulties. But it had ” lived long enough to found a family ” in subsequent coffee palaces and in the Men’s Institutes started by Miss Ellice Hopkins and Miss Daniells. Miss Boyd Bayly describes the frequenters of the ” Hall Haul All,” “carpenters, shoemakers, brick-layers, brickmakers, pig-feeders and plasterers . . . including ‘ Jimmie the Devil,’ the tall pig-feeder, who had been a hard drinker from sixteen till over sixty, and Taylor the navvy whose face, always bright, positively radiated beams when he got ensconced among his mates at the Hall. . • . Compared with the splendours of the modern coffee palace, the Hall was almost a barn for plainness, but it was jolly there.” Mr. Gell, the esteemed vicar of the parish, Mr. Roberts, pastor of Horbury Chapel, City missionaries and others took an active part in the work, and it is stated that from seventeen to eighteen hundred persons united themselves with various Christian communities in the neighbourhood. But the so-called ” Chaplain of the Hall,” was Mr. Henry Varley, the noted evangelist of later days, then a handsome young butcher in High Street, Notting Hill, who conducted services at the Notting Dale Chapel in \Valmer Road. This little building became so crowded that in 1864, with the help of his father-in-law, Mr. Varley built the Free, or West London Tabernacle, which, when enlarged in 1872, was capable of holding twelve hundred worshippers, and actually had an evening congregation of over one thousand. (The ” Taber-nacle ” and ” Tabernacle Hall ” which stood beside it in St. John’s, now Penzance Place, are at present used as business premises.)

Other religious bodies were at work in Notting Dale. In the eighteen-fifties a Convent was placed by the side of Pottery Lane and nuns were visiting the Irish Colony. At a later date they also cared for the group of Italians who came into the district when the slums of Drury Lane and St. Giles’s were cleared away. On the Feast of the Purification, 1860, a church and a school for girls were opened. This one-sided church, dedicated to St. Francis of Assisi, with its beautiful Gothic interior, was connected with St. Mary and the Angels, Bayswater, and was an outcome of Cardinal Wiseman’s Mission in London. It was built at the sole cost of the Reverend Father H. A. Rawes ; the architect was Mr. Clutten, but a much-admired Baptistery was added as a thankoffering, about f862, by Mr. Bentley, afterwards architect of the new cathedral at Wcstmi nster.9 By 1859 Norland Chapel was built at the junction of Queen’s, now Queensdale Road and Norland Road North, on part of the Latymer Estate, and the Baptist congregation under the Reverend John Stent came here from an old building facing Shepherd’s Bush. Before 1879 this chapel passed into the hands of the ” Christian Mission ” of the Rev. W. Booth, better known as the ” Salvation Army.” It was renamed ” Norland Castle,” and a good work has been carried on there ever since. In 1864 T. Powell, Esq., gave land for a Primitive Methodist Chapel, a yellow-brick building in Fowell Street, still in use ; Shaftesbury Hall, Portland Road was a City Mission Centre, and a party of Plymouth Brethren met in a room in Clarendon Place.

In the late fifties a project was started for connecting London and Hammersmith by a railway which should branch off from the Great Western Line at Green Lane Bridge (where Westbourne Park Station now stands), and cross Notting Hill in a south-westerly direction. The construction of the Hammersmith and City Railway influenced the development of the whole district. Hundreds of navvies were employed on the long series of high arches which were to carry the line over Latimer Road and the brick-fields then covering the site of the White City. As it was expected that the work would be in hand for some years, about three hundred of these railway navvies settled in the neighbourhood, and the erection of houses was rapidly pushed forward. Until 1860 Latimer Road had remained in a very countrified condition : ” a kind of hamlet,” cut off from the west by the embankment of the West London Junction Railway, and little accessible from other directions. But the chief drawback to locomotion lay in the deplorable condition of the unmade roads. In wet weather they were ” a mere swamp,” and in some places were entirely impassable. Many persons can remember the time when a horse could almost disappear in the ruts, and how, at the end of Walmer Road, laundry carts would sink up to their axles in the mud. On the morning of January 23, 1860, the body of a poor woman named Frances Dowling was found lying in the middle of Latymer Road. ” In returning to her home about eleven o’clock at night she had missed the crossing-place, and stumbled into one of the miry pits.” Cries for help had been heard, but drunken brawls were so frequent that no one troubled to get out of bed to investigate the cause.

In 1861 Mr. S. R. Brown was allocated by the London City Mission ” to visit in the new poor houses north of the Potteries.” A schoolroom, used for church services, had been closed for the building of the railway line, so that at that time neither church, chapel nor school existed on the district. A group of members of the “Workmen’s Hall” helped in organizing open-air services and house-to-house visitation, and a Mothers’ Meeting was started in the drying-room of a laundry. A committee was then formed of gentlemen living in the neighbourhood, with Dr. Gladstone as president, and George Maxwell, Esq., as hon. secretary ; land was obtained from Mr. Whitchurch, and the Latymer Road Mission Rooms were opened on February 23, 1863, as a Ragged Day and Sunday School and for devotional meetings of various kinds. The Mission Hall, with one small classroom attached, stood in the midst of a ” primaeval swamp, blossoming in broken bottles, pots and pans,” the only means of approach being a narrow track bordered by white posts, a necessary precaution on winter evenings. Two pathways were made by the mission helpers. One started close to the ” Lancaster Tavern,” at the junction of Lancaster and Walmer Roads, and the other from Mr. Brown’s house in Silchester Road at the corner of Lockton Street. It is believed that the strange bend at the northern end of Blechynden Street is due to the course of these pathways.

Up to this time the Latimer Road district had been considered as an outlying portion belonging to St. Stephen’s, Shepherd’s Bush, in the parish of Hammersmith. By 1864 it was evident that the northern part of St. James’s Norland in Kensington parish must be made into a fresh ecclesiastical district. Bishop Tait came down and held a service in ” Moore’s Field,” behind No. 125, Latimer Road, speaking to the assembled throng from the wash-mill mound of the disused brickfield. After this visit, schools and then a church were commenced. St. Clement’s schools were opened in 1866, and the adjoining church, designed by Mr. J. P. St. Aubyn, in 1867. The Rev. Arthur Dalgarno Robinson, curate of St. Stephen’s, Shepherd’s Bush, became incumbent, first of St. Andrews, an iron building at the junction of Lancaster and Walmer Roads, and afterwards of the new church : 1867 to 1881. St. Andrew’s Church was unfortunately burnt down, through overheating, on the last Sunday before St. Clement’s was opened. (In 1880 a handsome brick and stone Wesleyan Chapel was placed on this site.) Mr. Dalgarno Robinson collected large sums for St. Clement’s, and he also built a vicarage, surrounded by a garden with fruit trees, in the northernmost part of his parish. (This house, now in Dalgarno Gardens, subsequently became St. Helen’s vicarage.) From 1881 to 1886 the Rev. Edwyn Hoskyns, who in time became Bishop of Southwell, took over the work at St. Clement’s. Young and full of vigour, his influence soon made itself felt, and he gathered round him workers who came from the centre of Kensington. The parochial Relief Societies and the Mission Hall in Mary Place are due to his efforts. With the help of Miss Gore Browne the ” Lily Mission ” was started, chiefly as a centre for clubs for girls and for men. Miss Mason lived at the Lily Mission. Its name was changed to St. Agnes Mission when the building came under the manage-ment of the ‘West London Deaconesses. The influx of thousands of low-class inhabitants in 1862-1863, some attracted by the cheap rents charged in Notting Hill, some coming as an overspill of displaced populations from nearer the centre of London, turned parts of Norland Town into a slum area, even in those early days. Whole streets were not inhabited by the class of people for whom they were designed. Nevertheless, the portion of the district remaining within the parish of St. James’s, that is south of St. Katherine’s Road, now Wilsham Street, never sank so low as the St. Clement’s district, for the simple reason that St. James’s is not entirely composed of poor people. Indeed one of the clergy who worked there considers that it was an ideal parish between the years 1875 and 1892 when the Rev. Arthur Williamson was vicar. The parish contained five thousand poor, but in Mr. Williamson’s time there was a staff of ninety district visitors and a hundred and twenty Sunday School teachers, besides a Sunday congregation many of whom came from the large houses in Holland Park.

Further light on the growth of the neighbourhood is supplied by the dates at which various schools were built. In 1866, the year when St. Clement’s National School was opened, it had been found necessary to double the size of the Ragged School in Blechynden Street : ” Brown’s School ” as it was familiarly called. When in 1870 compulsory education became the law of the land, London was faced with an overwhelming problem. The fact that, by October 1873, a Board School for boys was opened in a hall in Crescent Street proves that, by that date, the population had far out-grown its school accommodation. A year later these boys moved with their headmaster, Mr. Williamson, to Saunders Road School, built on the Latymer Estate. In January 1875 the management of the school in Blechynden Street was handed over to the new Educational Authority ; four years later, on a rough winter’s evening in 1879, the Latimer Road Board School was opened, and the children were transferred to the new building across the way.’

This school was planned to hold twelve hundred scholars. Sixteen years earlier one hundred school places were deemed sufficient. Crescent Street Hall was again in use from March 1877 to July 188o, during the building of a large school in St. Clement’s Road. (Renamed Sirdar Road L.C.C. School, it has since that time been much enlarged by the addition of ” Centres ” and baths and a ” Special School.”) It is interesting to note that in 1874 Crescent Street Hall provided boys for a fairly high-class school, where a fee of twopence per week was charged, whilst in 1880 the same hall catered for children of a much lower type. St. Clement’s Road School was nicknamed ” The Penny Board,” and it was said that children were bribed there by the gift of sweets. Certainly they were extraordinarily rough, ragged and undisciplined. Whatever may be the verdict on the surrounding district, the children at least, have improved in tidiness and in their behaviour, especially during school hours.

The maps of 1868 and about 1880, on pages 154 and 158, show how this part of North Kensington was filling up. These pages are supposed only to chronicle events before 1880. But it seems a pity not to carry on the story of Notting Dale to the beginning of the present century. It was in 1882, a year after the most northern portion of St. Clement’s parish had been handed over to St. Helen’s, that the parochial district now belonging to Holy Trinity was formed. The large red-brick church in Latimer Road, which serves as the centre of the Harrow School Mission, was opened in 1884. It stands on land belonging to Hammersmith, although reckoned among Kensington churches. (St. Gabriel’s, Clifton Street, a daughter church of St. James’s, was originally in the same ecclesiastical position.) Most of the vicars of Holy Trinity have been old Harrovians. The first priest-in-charge, the Rev. William Law, had formerly been a curate at St. Mary Abbots’. With the backing of the school interest, and the help of many friends in Kensington, the Harrow Mission has become a very important agency for good, but its work chiefly belongs to modern times. At the request of the Rev. Edwyn Hoskyns a Boys’ Club was commenced by Mr. Arthur Walrond, an old Rugbeian, in a former woodyard in Walmer Road. In 1887 Rugby School made this club part of its Home Mission. The work has developed, and the Rugby Mission now owns good premises in Walmer Road. An earlier club, ” the Boys’Evening Shelter,” had been started at the Latymer Road Mission in 188o, when the rooms were no longer needed as school premises. The Latymer Crèche or Infant Day Nursery, which began at the same time, was a forerunner, a simple forerunner, of the great number of splendid agencies now connected with Infant Welfare. Public bodies have not been behindhand in attempts to reclaim the neighbourhood. A plot of four and a half acres, at one time brick land, in the centre of Notting Dale, was bought by the Kensington Vestry. Part of the ground was laid out by private munificence. Avondale Park, or the ” Rec ” as it is called locally, was opened in 1892, and has proved an immense boon. It comprises a flower garden, a bandstand and play-ground for children. In one corner stands a beautiful public Mortuary Chapel. Rent collecting by ladies was organized by Miss Octavia Hill, and has grown to large proportions since her death. For many years a branch of Kensington Workhouse stood in Mary Place behind the large police station. One of the first acts of the Kensington Borough Council in 1900 was to purchase a large part of Kenley Street, formerly William Street. During the mayoralty of Sir Seymour King a row of dwellings was put up, and other houses were adapted into workmen’s flats. A Home for District Nurses was placed in the same street, a Home in which the nurses, in 1903, ” were valiantly holding their own in spite of the disturbance caused by nightly brawls and the noisy and unsavoury Sunday markets.”

The Hon. Charles Booth 14 places the Kensington Potteries among the criminal and irreclaimable areas, largely on account of the overcrowded condition of its unsuitable and derelict houses. This Housing Problem has never been absent, though houses constructed without through ventilation, in which the toll of life was terrible in the cholera epidemic, have now been abolished by law.’ The advisability of opening up the blind alleys, in that part where the Hippodrome estate impinges upon Notting Dale, has been discussed again and again, but has not yet been accomplished. Five short streets in the district are known as the ” Special Area.” These streets are Bangor Street, Crescent Street and three roads that have been renamed, St. Clement’s, now called Sirdar Road, St. Katherine’s Road, now Wilsham Street, and William, now Kenley Street. In 1899 an enquiry was undertaken at the instance of the London County Council, and it was found that the rate of mortality in these particular streets differed little from the figures given for the Pottery District in 1856, and that nearly half the babies born in this area died before they were a year old.

In 1904 there was a public-house to every twenty-five dwellings in these streets, and about twenty-three common lodging-houses provided accommodation for over seven hundred persons, at a nightly charge of fourpence or sixpence. Greater however than the evil of these licensed lodging-houses, was, and still is, that of the furnished rooms let from the evening until ten o’clock the next morning at tenpence or a shilling a night. Such houses where ” the street doors are open day and night . . . inevitably lead to moral shipwreck ” (note 7). In the early years of this century there was a large working-class population in Notting Dale ” living cleanly by honest industry,” but, of a total of fifteen hundred families in the most congested portion, at least one thousand occupied one-roomed tenements furnished or unfurnished. Naturally overcrowding and pauperism go hand in hand ; to quote a recent publication on the subject, the ” moral results of this herding together of human beings are deplorable, and it is little to be wondered at that such conditions breed discontent and worse in those who suffer from them.”

With the advance of years the means of livelihood in Notting Dale have changed. Pigmasters and brickmakers no longer exist, railway navvies are gone, even hand laundry-work has declined in importance, although great steam-laundries still employ a small army of women. Cabmen and horse-keepers have largely disappeared. The men now chiefly work in factories or as casual labourers in various trades, whilst many manage to earn a livelihood as costermongers, rag-and-bone men, street hawkers, flower-sellers and ice-cream men. To this list must be added professional cadgers, thieves, corner-men and other professions of a less reputable character.’ The very nearness to a well-to-do neighbourhood is a source of temptation, for precarious earnings can be supplmented by begging. So a wife may dress herself as a widow, and a short time ago children used to be hired out to add pathos to the appeal for charity. A story is told of a curate who, seeing an old acquaintance, accosted him with the words : ” Why, Jones, you have got all your children of one size.” To which the man replied, ” Lor bless me, so I have, Sir. I must go back and change some of them ! ” It has been said that ” from the cradle to the grave the inhabitants rely first on the ever-ready gifts of the rich . . . ; and secondly, on the never-failing assistance of the Poor Law ” (note 7). Bad housing, and the inherited effects of alcoholism, improvidence and vice have tended to sap the vitality of the sons and daughters of the Dale. But other causes have contributed to its degradation. If the railway embankment of the West London Junction Railway had not cut off communication with the west, and if St. Clement’s Road had been carried through St. James’s Square, as was originally intended, instead of ending abruptly behind the houses, Notting Dale would not have been a backwater, and probably would never have become such a notorious ” Guilt Garden,” a sink for the dregs of other localities. But, in all fairness, it must be remembered that the special group of bad streets only covers a small area, and that the bulk of the population are hard-working, respectable citizens, although belonging to a low stratum of society. And, bad as many of the conditions still are, there is a degree of comfort and of reasonable enjoyment in the lives of most of the inhabitants undreamed of two generations ago. The district is not so black as it has been painted, and those who know it most intimately feel that a locality, where there is so much patient continuance in well-doing, should never have been branded with the name of the Kensington Avernus.

12 comments

Skip to comment form

My grandfather (Samuel Henley Horwood, born 1884) entered Saunders Road School in 1892. I was so moved to read about the living conditions in that part of London at that time. Thank you SO much.

This is a heartwarming read. It explains all one needs to know about living here. I felt the warmth and concern of people trying to help and the arrogance of some of people living here, bordering on the criminal. For me this has been, and is, a great place to live. Some wonderful people and also some who aren’t! I have always been interested in the large canvas of this area and the people who unwittingly created it and those who sought changes for the good of all.

Thank you so much, very informative, my grt grt grandad lived in latimer Road, 1850’s, he came over from Germany.

Thank you

hello xx

This was such an interesting read. My family the “Smith and Neivens” lived at 232 Latimer from the late 1800s right through to the 1980s, oh my how it has changed. xx

This is hugely interesting – thank you. My grandma was born in the area, and with her parents lived in Stebbing Street. Her father grew up in Clifton Street and Stebbing Street, and her mother in Bramley Road. To read about the evolution of the area is fascinating, and it is helpful to be able to appreciate the social context. My great grandfather was one of 10 children when the family lived in Clifton Street, and all but 4 of them died in infancy.

I had looked for the addresses on the Booth Poverty maps, and have read the notes from the accompanying notebooks, but this gives a much fuller picture of life in the area. Many, many thanks.

Thank you for this informative history. I lived in Saunders Grove from 1950 until it was slum cleared in1966.

Are there any maps of the Norland Estate and any pictures showing the houses and people would be great to see.

Regards Philip Green in Australia

Thank you for the history lesson. My 3x great grandmother and grandfather lived in 2 Adam’s cottages the potteries, Saunders road and Heathfield Street in the 1800s. I can’t even begins to imagine how hard it must have been back then. It reminds me how incredibly lucky some of us are now.

Thank you again.

I went to St James Norland 1953 to 1959 and well remember Miss (Denise) Sims, what a lovely lady.

My father’s family became part of the Poor Law. My grand-father died in 1913 (comment post earlier), leaving my grandmother (Georgina Marion Horwood, born Tedder) a widow with 3 children under the age of 5. Her two sons (my father, George Samuel and Henry Alfred) were taken to Marlesford Lodge, Hammersmith, to be looked after and received education – but my grandmother went to fetch them to take them home. They went to and fro many times. At the age of 7 they were taken to “Beecholme”, Fir Tree Lane, Banstead, Surrey (Banstead Road School; School District: Kensington and Chelsea School District). This changed their lives completely, as the two lads received food and good lodgings, plus an education (an education for ‘life’), under very strict conditions. ‘Life’ meaning that as well as a strict education, they learnt to cook, gardening, sewing, general house chores, woodwork. (Kensington and Chelsea was considered to be pioneers in this Pool Law venture). The downside? – visitors were only allowed for 2 hours a week, on Sundays.

Hi Sarah, mine have lived at number 254 since 1987.

Very informative article, thank you. My fathers family arrived at the potteries from Scotland in about 1882. So good to know more about the area. They actually resided in St Katherine Road now Wilsham St.. Again thanks.

Author

Thanks!